you’re snorkeling in crystal-clear waters when suddenly, an octopus glides past you with fluid grace. As you watch this magnificent creature propel itself through the water, you might wonder about the incredible biological machinery powering its movement. Here’s something that’ll blow your mind – that octopus cruising by actually has three hearts pumping blue blood through its body!

Most people assume octopuses have just one heart like humans, but the reality is far more fascinating. Understanding how many hearts does an octopus have opens up a window into one of nature’s most ingenious circulatory systems. In this deep dive, we’ll explore why these intelligent cephalopods evolved with multiple hearts, how each one functions, and what makes their blue blood so special.

Why Does An Octopus Have Three Hearts?

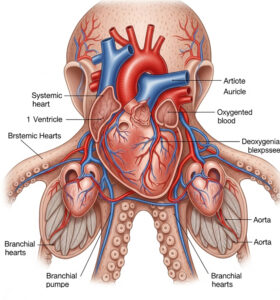

The octopus’s three-heart system isn’t just biological overkill – it’s an evolutionary masterpiece designed for survival in challenging ocean environments. Two of these hearts, called branchial hearts, work exclusively to pump blood through the gills, while the third, larger systemic heart circulates blood throughout the rest of the body.

This setup exists because octopuses rely on copper-based blood (hemocyanin) instead of iron-based blood like humans. Copper-based blood is less efficient at carrying oxygen, especially in cold ocean depths where many octopuses live. Having multiple hearts compensates for this inefficiency by maintaining adequate blood pressure and circulation.

The Anatomy of Octopus Hearts

Each of the three hearts serves a specific purpose:

Branchial Hearts (2):

- Located near each gill

- Pump deoxygenated blood through gill filaments

- Increase pressure for efficient oxygen exchange

- Continue beating even when the systemic heart stops

Systemic Heart (1):

- Larger and more muscular

- Pumps oxygenated blood throughout the body

- Supplies the brain, arms, and internal organs

- Stops beating when the octopus swims actively

How The Three-Heart System Actually Works

Here’s where things get really interesting. When an octopus is resting on the ocean floor, all three hearts work in harmony. The branchial hearts push blood through the gills to collect oxygen, while the systemic heart distributes that oxygen-rich blood to vital organs.

But when the octopus needs to swim – perhaps to escape a predator or hunt for food – something remarkable happens. The systemic heart actually stops beating during active swimming! This means the octopus relies entirely on its two branchial hearts for circulation while moving.

This explains why octopuses prefer crawling along the seafloor using their arms rather than swimming. Extended swimming sessions exhaust them quickly because their main heart isn’t helping with circulation.

The Mystery of Blue Blood

One of the most striking features of octopus biology is their blue blood, which directly relates to why they need three hearts. Instead of iron-rich hemoglobin (which makes human blood red), octopuses use copper-rich hemocyanin to transport oxygen.

| Feature | Human Blood | Octopus Blood |

|---|---|---|

| Color | Red | Blue |

| Oxygen carrier | Hemoglobin (iron) | Hemocyanin (copper) |

| Efficiency | High in warm conditions | Better in cold, low-pH conditions |

| Hearts needed | 1 | 3 |

Hemocyanin works exceptionally well in cold, acidic ocean environments where these creatures thrive. However, it requires higher blood pressure to function efficiently – hence the need for multiple hearts working together.

Real-World Implications and Fascinating Facts

During my research on marine biology, I’ve learned that octopus hearts can beat anywhere from 30-36 times per minute when resting, but this can increase dramatically during stress or feeding. What’s particularly fascinating is that the branchial hearts are so efficient, they can maintain basic circulation even if the systemic heart is damaged.

This redundancy system has inspired medical researchers studying artificial heart design. Some scientists are exploring whether multi-heart systems could help patients with severe cardiac conditions.

Temperature and Heart Function

Ocean temperature dramatically affects octopus heart performance. In warmer waters, their hemocyanin becomes less efficient, forcing the hearts to work harder. This is why you’ll find the largest octopus species in colder waters – their three-heart system performs optimally in these conditions.

Conversely, in very cold waters, the copper-based blood actually becomes more effective at oxygen transport than iron-based blood would be, giving octopuses a significant advantage over many other marine animals.

What Happens When One Heart Fails?

Octopuses show remarkable resilience when one heart is damaged. If a branchial heart stops working, the remaining branchial heart and systemic heart can compensate, though the octopus may become less active. However, if the systemic heart fails, survival becomes much more challenging since it’s responsible for supplying the brain and other vital organs.

Interestingly, octopus hearts have some regenerative capabilities, though not to the extent of their famous arm regeneration. Minor heart damage can sometimes heal over time, especially in younger specimens.

Conclusion

The next time you see an octopus in an aquarium or nature documentary, remember that you’re looking at one of nature’s most sophisticated circulatory systems. How many hearts does an octopus have? Three remarkable organs working in perfect coordination to keep these intelligent creatures alive in some of Earth’s most challenging environments.

This three-heart system represents millions of years of evolutionary refinement, solving the unique challenges of life in cold ocean depths with copper-based blood. It’s a reminder that nature often finds ingenious solutions that seem almost too clever to be real.

Have you ever wondered about other amazing octopus adaptations? Share your thoughts in the comments below, or explore more fascinating marine biology facts on our site!

Frequently Asked Questions

Do all octopus species have exactly three hearts? Yes, all octopus species have three hearts – two branchial hearts and one systemic heart. This is a fundamental characteristic of all cephalopods in the octopus family.

Can an octopus survive if one of its hearts stops working? Octopuses can survive with one damaged branchial heart, though their activity levels may decrease. However, systemic heart failure is typically fatal since it supplies blood to the brain and vital organs.

Why does the main heart stop when octopuses swim? The systemic heart stops during swimming due to the physical stress and positioning changes that occur during active movement. This forces octopuses to rely on their branchial hearts alone, which is why they tire quickly when swimming.

Is octopus blue blood poisonous to humans? No, octopus blood isn’t poisonous to humans. The blue color comes from copper-based hemocyanin, which is harmless. However, some octopus species do have venomous saliva that’s separate from their blood.

How fast do octopus hearts beat? Octopus hearts typically beat 30-36 times per minute at rest, though this can increase significantly during activity, feeding, or stress. The rate varies between species and environmental conditions.

Do squid and other cephalopods also have three hearts? Yes, squid, cuttlefish, and nautiluses also have similar multi-heart systems, though the exact configuration may vary slightly between species. This is a shared characteristic of the cephalopod family.